by Kenton Shepard and Nick Gromicko, CMI®

The purpose of the series “Mastering Roof Inspections” is to teach home inspectors, as well as insurance and roofing professionals, how to recognize proper and improper conditions while inspecting steep-slope, residential roofs. This series covers roof framing, roofing materials, the attic, and the conditions that affect the roofing materials and components, including wind and hail. We won’t go into attic inspection too deeply since this series of articles from Mastering Roof Inspections is primarily about roofing defect recognition, but you should have an understanding of the two main, basic roof structure systems: conventional roof framing and roof trusses.

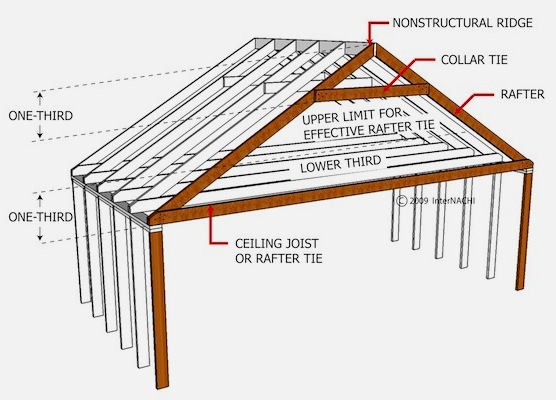

You’ll be evaluating the roof framing from inside the attic space, but we have an advantage in technology. Let’s strip away the roof and wall coverings of a home and identify some of the more common roof framing members. We’ll start with a conventionally framed roof in which individual roof-framing members are cut and assembled on-site.

CONVENTIONAL ROOFS

Conventional Roof Framing

Common Rafters

Rafters which rest on the outside walls at the bottom and connect to the ridge at the top are called “common rafters” (highlighted here in yellow).

Rafters on opposite sides of the ridge should be installed directly opposite each other in pairs -- although, if you see a few that don’t align, it’s really not a defect. Rafters sometimes have to be moved a little to accommodate components of other home systems. The illustration above shows a rafter moved to accommodate a combustion vent.

If you see many rafters that don’t align, you may comment on this, but in existing homes, refrain from calling it a defect unless you see failure. In newer homes, many rafters which don’t oppose usually indicate poor-quality framing. It’s an indication that you should look carefully for other problems in the roof framing.

Rafters are typically installed on 24-inch centers. If you see rafters installed on centers greater than 24 inches, look for signs of failure, such as sagging of the rafters. If you see sagging rafters, recommend stabilization by a qualified contractor. Stabilization typically involves installation of a purlin system.

Hips

Hip roofs have “hip rafters” which are oriented diagonally to the ridge and outside walls. Hip rafters are simply called “hips,” and are shown here as brown. Hips rest on an outside corner at the bottom and connect to the ridge at the peak.

Rafters which rest on the exterior walls at the bottom and connect to a hip at the top are called “hip jacks,” shown here as purple.

Valleys

Where ridges change direction, an inside corner is created, which is spanned by a “valley rafter” or simply “valley,” shown here as green. Valleys are also oriented diagonally to the ridge and exterior walls. Valleys rest on top of the walls at the inside corner at the bottom, and connect to the ridge at the top.

Rafters which connect to the valley at their bottoms and connect to the ridge at the top are called “valley jacks,” shown here as light blue.

Conventional Ridge

The illustration shows a conventional ridge (colored orange). In homes with conventional ridges, the rafters support the weight of the roof and transmit the roof load down through the walls to the foundation and, finally, to the soil. The route taken by the weight of the roof through the framing members to the soil is called the “load path.”

The purpose of the ridge is to provide an easy method for connecting rafters at the peak of the roof, and to provide better nailing at the peak.

Older homes may have no ridge at all. That was a common building practice at one point in various parts of North America, and it’s not a defect as long as the rafters oppose each other.

Engineered lumber used for roof framing has very specific requirements for connections, and discussing them here exceeds the scope of this series. The manufacturers of metal connectors for engineered lumber publish connection specifications in their catalogues and on their websites.

Rafter Ties

In homes with flat ceilings and an attic space, the bottoms of opposing rafters should be fastened together with ceiling joists, which form “rafter ties.” When rafters have been installed perpendicular to the ceiling joists, rafter ties typically rest on top of the ceiling joists.

Rafter ties prevent the weight of the roof from spreading the tops of the walls and causing the ridge to sag.

Collar Ties

Collar ties connect the upper ends of opposing rafters. They should be installed on every other rafter in the upper third of the roof. Their purpose is to prevent uplift. Whether or not they should be installed is an engineering call. They aren’t always required so the lack of them is not a defect, but when you see them, they should be installed correctly.

Here, you can see collar ties installed in the upper third of the roof, and rafter ties installed down low and spliced over a wall.

Purlin Systems

You can also see the purlin system.

Purlin systems are designed to reduce the distance that rafters have to span. They consist of strongbacks nailed to the undersides of the rafters and supported by diagonal braces.

The bottoms of purlin braces should rest on top of a bearing wall. Braces that rest on ceiling joists or which somehow pass the roof load to the ceiling below are defective installations. If you see braces which rest on ceiling joists, look for a sag in the ceiling.

Braces are typically installed every other rafter and should be at an angle no steeper than 45°.

Here’s a purlin system installed in the garage of an older home. With no central wall to carry the braces, they bear on a strongback that rests on the ceiling joists. There was no sagging, so there was no comment in the inspection report.

Purlin systems have been built in many ways -- some better than others. Modern building codes call for strongbacks to be of equal or greater dimension than the rafter dimension, but most purlin strongbacks you’ll see will not meet this requirement. If you know that the home was required to meet this code when it was built, call it a defect; otherwise, limit your inspection to looking for signs of failure, such as sagging or broken rafters and broken components. Also, look for improper installations, such as braces resting on ceiling joists, braces but no strongback, and too few braces.

In older homes in some areas, it’s common to find no strongbacks. It’s a quality issue unless the roof is sagging; then, it’s a structural issue and you should recommend stabilization by a qualified contractor.

The term “purlin” has several different meanings depending on what part of North America you’re in, what part of the roof you’re talking about, and the background of the person you’re discussing it with, so don’t be surprised if someone tries to correct you.

Structural Ridge

Homes with vaulted ceilings usually don’t have rafter ties to keep the walls from spreading and the ridge from sagging, so they use a structural ridge. In a home with a structural ridge, the ridge consists of a beam strong enough to support the roof load without sagging.

Overframe

When you’re inside an attic, you may see a condition in which the ridge and a few jack rafters from one roof section are framed on top of an existing roof.

This is called an “overframe” and it’s quite common in certain areas. Built correctly, it’s structurally sound.

You’ll often see a section of roof sheathing removed to provide a passageway between attic spaces. If you can’t enter a portion of the attic, recommend that it be inspected by a qualified inspector after access is provided. This is especially important if it contains plumbing or electrical components.

**************************************************