Inspecting for Foundation Damage from Expansive Soils

by Nick Gromicko, CMI® and Kenton Shepard

Home inspectors should be aware of the geological characteristics that are specific to their region. Along with local climate and typical weather patterns, knowledge of the local geology can help inspectors understand how the building materials of the homes they inspect can be affected. One of these important characteristics is expansive soils.

What is expansive soil?

Expansive soils are fine-particle, clay-based soils that expand in volume when they are exposed to water. Different clay types have different expansive characteristics.

Expansion is caused by an electro-chemical attraction between water molecules and fine clay particles. Materials consisting of fine particles have greater surface area than materials containing large particles, and because clay has a lot of surface area per given volume, it attracts a lot of water. Water attaching to particle surfaces without being absorbed by them happens through a process called adsorption. Surface tension is a contributor to this process.

Expansive soils can damage foundations and concrete floor slabs through uplift or lateral expansion. In a typical year in the U.S., expansive soil causes greater financial loss than than hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, and tornados combined.

Soils capable of damaging foundations may contain as little as 5% of the active mineral, and may exert as much as 5,500 pounds per square foot of pressure (psf) against the concrete.

Regions in the U.S. with expansive soil

(Image credit: “Swelling Clays Map of the Conterminous United States” by

W. Olive, A. Chleborad, C. Frahme, J. Shlocker, R. Schneider and R. Schuster,

published in 1989 as Map I-1940 in the USGS Miscellaneous Investigations Series)

Map Key

- PINK: Over 50% of these areas are underlain by soils with abundant clays with high potential for swelling.

- BLUE: Less than 50% of these areas are underlain by soils with clays with a high potential for swelling.

- ORANGE: Over 50% of these areas are underlain by soils with abundant clays having a slight-to-moderate potential for swelling.

- GREEN: Less than 50% of these areas are underlain by soils with abundant clays with a slight-to-moderate potential for swelling.

- BROWN: These areas are underlain by soils with little to no clay with potential for swelling.

- YELLOW: Data is insufficient to determine the clay

content or the potential for soil swelling.

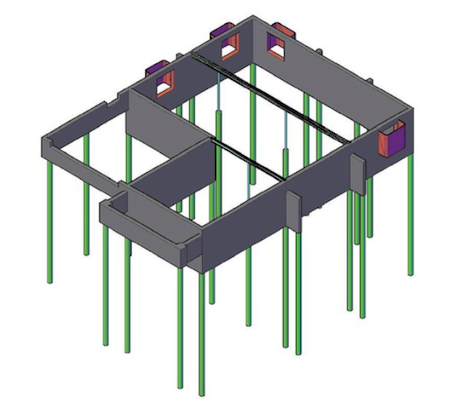

Special Building Methods

Special methods must be used when installing a foundation on expansive soil in order to avoid future damage as the soil expands. One method is to rest the foundation on piers that extend down below the zone of water-content fluctuation, where the soil is stable, or down to bedrock.

Drilled pier foundation

(Image used with permission from EVStudio.com)

Piers that extend to stable soil but don't rest on bedrock may rely on friction instead of direct bearing to support the structural load.

Walls of this drilled-pier

foundation will be poured over sacrificial void forms.

(Photo courtesy of Kenton Shepard)

In the photo above, holes at the corners and mid-spans of the walls will be filled with reinforced concrete to form piers. The top 3 feet of rebar are visibly protruding from the holes. Sacrificial cardboard void forms placed on the ground between the piers and forms are strong enough to bear the weight of the concrete when it is poured, creating voids beneath the walls. If the soil heaves, the void forms will be crushed. The amount of heaving will have to be greater than the thickness of the void forms (typically, 6 inches) for the soil to come into contact with the bottom of the foundation walls.

Void forms after the walls have

been poured

(Photo courtesy of Kenton Shepard)

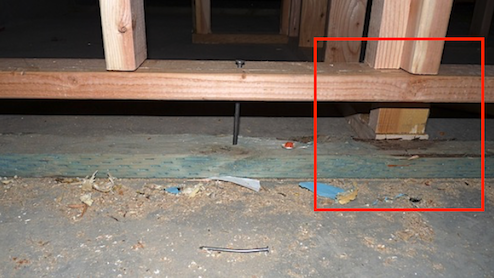

Doubled or floating bottom plate

accommodates heaving.

(Photo courtesy of Kenton Shepard)

Floating Plates

Another method used to accommodate heaving is the use of doubled or floating bottom plates. When inspecting a home in an area known to have expansive soil, inspectors should identify basement walls framed without this method as defective. In a newer home, inspectors should recommend that corrections be made. If walls have been in place for a significant period of time with no damage occurring, this condition will probably not be a problem unless something happens that introduces water into the soil beneath the basement floor. This might be a leak from plumbing pipes, valves or fixtures, or leaking of laundry appliances. Inspectors should state this in their reports.

A floating bottom plate wall connected to an intersecting wall

with a single bottom plate

(Photo courtesy of Kenton Shepard)

The photo above shows a wall with doubled bottom plates connected to a wall with single bottom plates. Heaving will damage the connection between the two walls, and the walls with the single bottom plates may transfer the force of the heaving to the home’s structure above. This should be identified as a defect in the inspection report. If the walls have been in place for many years, the chances are good that unless changes occur that introduce moisture into the soil beneath the slab, such as plumbing leaks, no problem will result, and this should be mentioned in the report. In newer homes, this condition may cause problems, and that should be stated in the report.

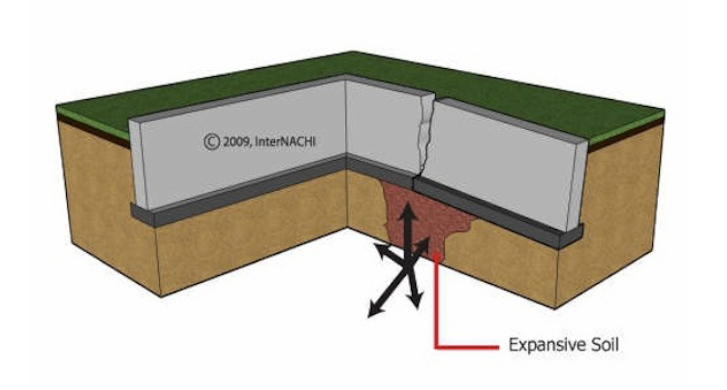

This cracking was caused by expansive soil.

(Photo courtesy of Kenton Shepard)

Soil expansion severe enough to cause cracking should be apparent during an inspection. In the photo above, it was possible to feel the high spot at the crack by walking across the floor.

Cracks caused by heaving may be wider at the top, as shown in the illustration above, but this condition can also be caused by settling toward one corner.

Vertical displacement creates trip hazards, and you may see concrete ground down to alleviate this problem, as in the photo above. Inspectors who observe these types of trip hazards should recommend correction. In areas with expansive soils, inspectors need to be diligent in identifying negative and neutral grade around the foundation and recommending mitigation. Typical mitigation involves correcting the grade and/or installing a plastic membrane beneath the topsoil around the home’s perimeter to act as a barrier to runoff seeping down next to the foundation.

Summary

As a home inspector, whether you're performing phase inspections on a new-construction home or inspecting an existing home, the surrounding terrain and local geology will give you much information about what to look for at the foundation, basement, and overall structure. Although diagnosing the cause of structural issues falls outside the InterNACHI Standards of Practice, you can convey information about expansive soils to your clients, especially those who live in a Pink or Orange Zone, to alert them about the potential problems that are caused by them. As always, recommend follow-up by a soil or structural engineer.

Take InterNACHI's free, online "Fundamentals of Inspecting the Exterior" video course.

Take InterNACHI's free, online "Exterior Safety for Inspectors and Contractors" video course.

Take InterNACHI's free, online "How to Inspect for Moisture Intrusion" course.

Inspecting Residential Lot Drainage in Areas with Expansive Soils

Soils and Settlement

Moisture Intrusion

Soil Contamination Inspection

Read more inspection articles like this.

Download your free copy of STACKS: A Home Inspector’s Guide to Increasing Gross Revenue.

Download your free copy of SLEEP WELL: A Home Inspector’s Guide to Managing Risk.

BizVelop: Free Business Development Tool for Home Inspectors