Inspecting Added Blown Insulation in an Existing Vented Attic

by Nick Gromicko, CMI® and Ben Gromicko

According to the InterNACHI Standards of Practice for Performing a General Home Inspection, a home inspector is required to inspect the insulation in the attic and describe the type and approximate average depth of insulation observed at the unfinished attic floor area. Because most heat loss in a home is through the attic, increasing attic insulation is one of the most cost-effective steps homeowners can take to improve home energy efficiency. Adding insulation will help provide added thermal protection and enhanced comfort. Let's learn about what a successful installation of additional insulation in a vented attic looks like.

According to the InterNACHI Standards of Practice for Performing a General Home Inspection, a home inspector is required to inspect the insulation in the attic and describe the type and approximate average depth of insulation observed at the unfinished attic floor area. Because most heat loss in a home is through the attic, increasing attic insulation is one of the most cost-effective steps homeowners can take to improve home energy efficiency. Adding insulation will help provide added thermal protection and enhanced comfort. Let's learn about what a successful installation of additional insulation in a vented attic looks like.Many older homes have little or no attic insulation. Loose-fill insulation, such as blown cellulose or blown fiberglass, can be installed at the ceiling plane/attic floor to improve thermal performance in a vented attic. Care should be taken when installing blown insulation to ensure that it fills all ceiling joist bays, leaving no gaps or voids around wiring or piping, and that it covers the tops of the joists to stop thermal bridging. The depth of coverage should be even across the field of the attic.

The ceiling plane or attic floor should be thoroughly air-sealed prior to installing insulation. Robust and continuous air control is critical to a high-performance thermal enclosure. The existing insulation must be removed to provide access to the ceiling plane for air sealing. Debris and dust should also be removed so that sealants will have good adhesion. All cracks, seams and holes should be sealed using caulk or spray-foam sealants.

The photo above was taken at InterNACHI's House of Horrors® in Boulder, Colorado. At this inspection training facility, there's missing air sealant at the duct vent, as seen from the attic.

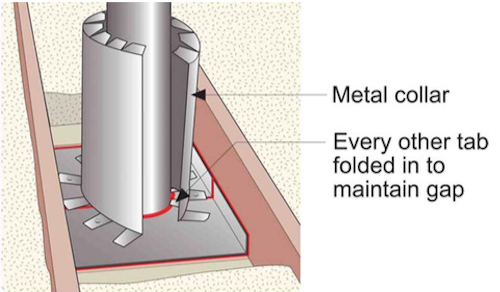

Solid blocking should be used at any larger holes and open soffits. Metal blocking and collars can be constructed around hot flues to keep the insulation from touching them. Covers can be purchased or constructed to cover, air-seal, and insulate recessed can lights that are not insulated ceiling airtight (ICAT)- rated.

Figure 1. Metal blocking and collar around a flue pipe

Figure 2. Sealant around a light fixture

If existing insulation was removed from the attic floor to perform air sealing, it may be reinstalled if it is in good condition. However, existing attic insulation is often contaminated with construction debris, plaster scraps, animal droppings, etc. Older loose-fill may be vermiculite insulation, which can contain asbestos. The safest approach may be to dispose of the old insulation and install only new insulation.

Figure 3. Attic Insulation Requirements per the 2009 and 2012 IECC

The presence of flooring above the ceiling joists in an attic will make it difficult to air-seal at the ceiling plane (attic floor). If the air control is to be established at the ceiling plane, then any attic flooring installed above must be removed to provide full access to the ceiling surface. In some cases, floor sheathing may resist the lateral thrust of roof framing. If floor sheathing is attached to framing that is perpendicular to the slope of the roof (perpendicular to the ridge or eave), the sheathing should not be removed without first consulting a qualified building professional. Alternately, it may be possible to transition the air barrier to the top of the existing attic floor. To successfully execute this option, sufficient insulation is required outboard (on top of) the floor to control condensation, and a robust air-control connection must be made from the top of the exterior walls to the perimeter of the attic flooring.

In Climate Zones 6 or higher, a Class I vapor barrier (e.g., polyethylene) or Class II vapor retarder should be installed above the ceiling drywall, as required by code. Class I vapor barriers should be avoided in Climate Zones 5 and below, as condensation can form on the attic side of the vapor barrier in summer months during regular use of air conditioning.

Figure 1. Metal blocking and collar around a flue pipe

Figure 2. Sealant around a light fixture

If existing insulation was removed from the attic floor to perform air sealing, it may be reinstalled if it is in good condition. However, existing attic insulation is often contaminated with construction debris, plaster scraps, animal droppings, etc. Older loose-fill may be vermiculite insulation, which can contain asbestos. The safest approach may be to dispose of the old insulation and install only new insulation.

Figure 3. Attic Insulation Requirements per the 2009 and 2012 IECC

The presence of flooring above the ceiling joists in an attic will make it difficult to air-seal at the ceiling plane (attic floor). If the air control is to be established at the ceiling plane, then any attic flooring installed above must be removed to provide full access to the ceiling surface. In some cases, floor sheathing may resist the lateral thrust of roof framing. If floor sheathing is attached to framing that is perpendicular to the slope of the roof (perpendicular to the ridge or eave), the sheathing should not be removed without first consulting a qualified building professional. Alternately, it may be possible to transition the air barrier to the top of the existing attic floor. To successfully execute this option, sufficient insulation is required outboard (on top of) the floor to control condensation, and a robust air-control connection must be made from the top of the exterior walls to the perimeter of the attic flooring.

In Climate Zones 6 or higher, a Class I vapor barrier (e.g., polyethylene) or Class II vapor retarder should be installed above the ceiling drywall, as required by code. Class I vapor barriers should be avoided in Climate Zones 5 and below, as condensation can form on the attic side of the vapor barrier in summer months during regular use of air conditioning.

Figure 4. Climate Zones taken from Figure C301.1 of the 2012 IECC

One benefit of a vented rather than unvented attic is that interior-sourced moisture will be vented out of the attic space before causing damage to the roof sheathing. Another advantage of vented attics in cold climates is that they help to reduce the chances of ice dam formation on the roof. Ice dams occur when heat leaks from the conditioned space (through holes in the ceiling plane, insufficient insulation, or heat loss from ductwork) and melts the snow on the roof. This melted snow travels down to the edges of the roof, where it refreezes, creating icicles and ice dams. Attic ventilation helps to “flush away” this heat before it can melt the snow.

Figure 5. Ice dam

The vented attic approach requires that there be sufficient height at the attic eaves for code-level required amounts of insulation. In mixed and cold climates (Climate Zones 4 and above), inadequate insulation raises the risk of wintertime condensation forming at the top plate due to cold surfaces. If the roof is too low at the eaves to install adequate amounts of blown insulation, then alternative solutions include filling the space over the top plate up to the baffle with closed-cell spray foam, or covering the top plate area with rigid foam board. (Spray foam and rigid foam have higher R-values per inch than blown insulation. Spray foam has the added advantage of air sealing the top plate-to-drywall seams and the baffle-to-top plate seam.) Another option is to convert the attic to a sealed insulated space by sealing the soffit vents and insulating along the underside of the ceiling deck with closed-cell spray foam or above the roof deck with rigid foam. In new home construction, a common solution to increase the roof height for insulation above the top plate is to use raised heel trusses. Older existing roofs are unlikely to have raised heel trusses, and they are not likely to be installed as a retrofit measure unless a complete reconstruction of the roof is required, such as when, for example a second or third story is being added.

The vented attic approach requires that there be sufficient height at the attic eaves to maintain an air gap above the insulation for ventilation air traveling from the soffit vents to the ridge vents. The vent space should be at least 2 inches high as well as throughout the width of the framing bay at each soffit vent. Baffles should be installed at each soffit vent to provide this pathway for ventilation air to move up past the insulation along the underside of the roof deck to the ridge vents or mushroom cap vents located near the ridge. The lower edge of the baffle can be sealed to the attic floor at the outside edge of the top plate with spray foam, which also air-seals the top plate-to-drywall seams. The baffles also serve to prevent insulation from covering the soffit vents, and they can also prevent “wind washing,” i.e., when wind blows in the soffit vents and pushes the insulation back from the eaves.

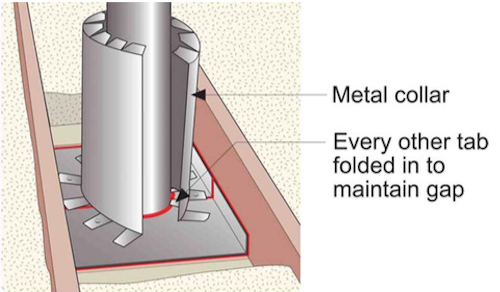

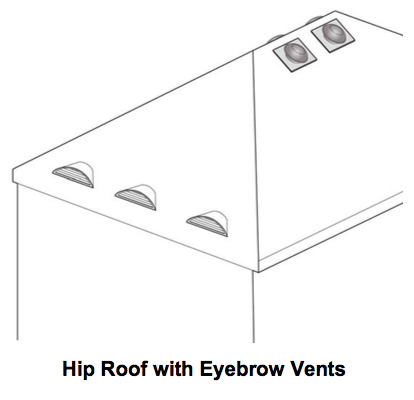

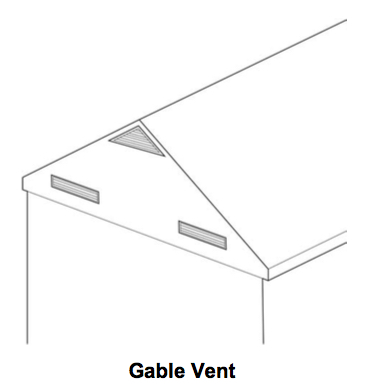

If the attic does not have soffit vents, attic ventilation can be provided by installing other types of vents, such as gable or eyebrow vents, down low near the attic floor or along with ridge vents, or by installing mushroom cap vents up near the roof ridge.

Using powered attic ventilators (which are thermostatically controlled fans that exhaust attic air during hot weather) can result in increased infiltration, and associated higher cooling loads. Studies have shown that powered ventilators consume more electricity than their associated savings through air conditioner use.

Installing HVAC ducts and air handlers in vented attics is not recommended. Locating ductwork and/or air-handling equipment in a vented attic can contribute to energy losses, performance issues, and ice dam formation in snowy climates, especially if the ducts and air handlers are leaky or poorly insulated. One exception is if the ductwork can be encapsulated in spray foam and buried beneath the attic floor's blown insulation. The ducts must be tightly air-sealed and covered with a sufficient amount of spray-foam insulation to minimize the risk of condensation forming on the outside of the ducts. However, because mechanical equipment, such as air handlers, cannot be adequately air-sealed, locating them in a vented attic is not recommended. If the air handler must be located in the attic, then converting the attic to a sealed insulated space should be considered.

Figure 6. Vented attic with loose-fill, fibrous insulation at the attic floor

Recommended Method for Insulating an Attic Floor with Blown Insulation

- Before any retrofit work is done, the work area should be inspected for active knob-and-tube wiring, bathroom fans venting into the attic, roof leaks, and other hazardous conditions. These conditions should be repaired prior to adding insulation. Hazardous materials, such as asbestos-containing vermiculite insulation, should be inspected for and removed or remediated.

- Any existing insulation, debris and dust should be removed, and the work area should be cleaned to allow for an adequate adhesion of sealant.

Figure 7. Clean the attic floor of debris prior to installing new insulation. Use baffles to provide a path for the ventilation of air entering the attic from the soffit vents.

Figure 8. Seal drywall-to-top plate seams. Seal the lower edge of the baffle to the top plate to prevent incoming air from the soffit vents from flowing under the baffles and into the insulation.

Figure 9. Seal all ceiling joists, drywall-to-top plate seams, and penetrations at the attic floor.

- All ceiling joints and penetrations should be sealed with sealant. The top plate-to-drywall seams and top plate-to-baffle seams should be sealed. Additional solid blocking should be provided for large holes and open soffits. Metal blocking and collars should be installed around hot flues. Covers should be installed over non-ICAT-rated recessed can lights. Intentional openings, such as combustion air ducts and soffit, ridge and gable vents, should not be blocked. Visual inspection, infrared thermography, and blower-door testing are all tools that could be used to verify air barrier continuity.

Figure 8. Seal drywall-to-top plate seams. Seal the lower edge of the baffle to the top plate to prevent incoming air from the soffit vents from flowing under the baffles and into the insulation.

Figure 9. Seal all ceiling joists, drywall-to-top plate seams, and penetrations at the attic floor.

- Proper ventilation of the attic provided by soffit and ridge vents or eyebrow, gable end, mushroom cap, and/or other vents should be verified (see Figure 5). If soffit vents exist, inspect the existing baffles and install new baffles, if needed (see Figure 3).

Figure 10. Four attic venting approaches for vented attics that don’t have soffit vents. The vents are installed low for incoming air, and installed high for outgoing air.

- Install loose-fill fibrous insulation over the attic floor to levels that meet or exceed the current adopted building and energy codes for thermal performance. The entire ceiling all the way to the top plate should be covered to provide adequate thermal resistance. The depth of the fibrous insulation should be as even as possible.

Figure 11. Loose-fill fibrous insulation is installed against the baffle to full code-required insulation height.

Summary

A home inspector is required to inspect the insulation in the attic and to describe the type and approximate average depth of the insulation observed at the unfinished attic floor area. Increasing attic insulation is one of the most cost-effective steps homeowners can take to improve their home's energy efficiency. A home inspector can know what a successful installation of additional insulation in a vented attic should look like.

Take InterNACHI's free, online How to Inspect the Attic, Insulation, Ventilation and Interior course.